Garry oak ecosystems

In British Columbia, the Garry oak (Quercus garryana) is categorized as a small to large-sized deciduous broadleaf tree, dependent on its growing conditions. Garry oak is in the Fagaceae family, and is sectioned with white oaks (Quercus sect. Quercus). Characterized by a broad, rounded crown, Garry oaks are known for stout, often forked stems, twisted branches, and dark grayish-brown, scaly bark with shallow furrows. Deeply lobed leaves are bright green and glossy above and paler with red to yellow hairs underneath. The leaves turn brown in the fall. Garry oaks bear single or paired acorns with a shallow, saucer-shaped cap. Trees can grow up to 30 m in deep soils and shrubby on rocky, shallow soil sites. Garry oaks are long-lived, up to 200 years with older specimens observed. Notably, Garry oak is not grown for timber production but woodworkers are increasingly utilizing large, old urban Garry oaks for fine furniture making.

Garry oak ecosystems are a subcomponent of the Coastal Douglas-fir ecosystem. Garry oak trees are the only native oak in British Columbia and are found at low elevations (sea level to 1,800 metres) in deep meadow soil, and on dry, rocky slopes with shallow soil.

Colonial Scottish botanist David Douglas assigned the English name of Garry oak for his friend Nicholas Garry, who was the deputy governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1822-1835. This oak species is also referred to as the Oregon white oak in the United States. The lək̓ ʷəŋən word for Garry oak ecosystem is Čaŋēɫč or Kwetlal. The SENĆOŦEN word for Garry oak is ĆEṈ¸IȽĆ and pronounced Chung-ae-th-ch, and the HUL’Q’UMI’NUM word is p’hwulhp.

Source

Ministry of Forests, Government of BC. Tree Book: Garry oak. https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/library/documents/treebook/garryoak.htm

Forestry Service, National Resource Canada, Government of Canada. (modified 2024-11-12). Forest Resources: Trees, insects, mites, and diseases of Canada’s forests: Trees: Index of Trees: Garry oak. https://tidcf.nrcan.gc.ca/en/trees/factsheet/308

Klinkenberg, Brian (Editor). Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. (2020) E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants of British Columbia [eflora.bc.ca]. [Accessed: 2026-01-14]. https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Quercus%20garryana

Canadian Woodworking. Tucker, John. (2018). Vancouver Island Woodworkers Guild’s Wood Recovery Program.

The Kwetlal food system or Garry oak ecosystem is a living artifact of the Indigenous peoples who took care of this land for generations. It is dominated by twisted, gnarled Garry oak trees and includes a mosaic of individual trees, fragmented stands of trees, woodlands, parklands, meadows, grasslands, scattered Douglas-fir stands, and open rocky areas. The forest understory is composed of shrubs, wildflowers, and other plants. At least 1,645 organisms (plants, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) have co-evolved within this unique ecosystem.

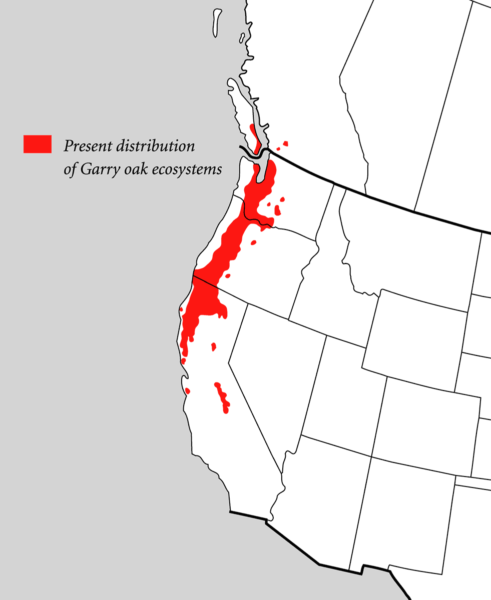

Garry oak ecosystems are among the most endangered ecosystems in Canada, with only five percent remaining in a natural state. In Canada, they occur only on the southeastern tip of Vancouver Island and adjacent Gulf Islands, plus two isolated groves east of Vancouver. A rare wetland Garry oak stand is found in Courtenay’s Vanier Nature Park, and the northerly population extends as far as Campbell River.

Source

Erickson, W. Conservation Data Centre, Wildlife Branch. BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. (1993). Ecosystems in British Columbia at Risk Series: Garry oak Ecosystems. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/conservation-data-centre/publications/erickson_garry_oak.pdf

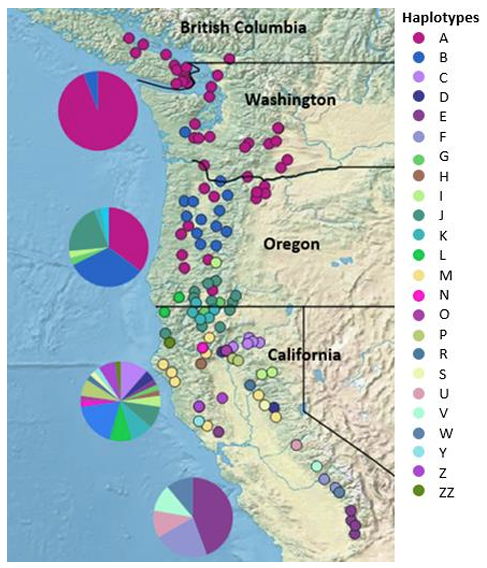

Garry oak woodlands are an important link to the past. Garry oak distribution has ebbed and flowed between the ice ages. Genetically the Garry oaks around the Salish Sea and the inland marine waterways of Washington and British Columbia belong to a single haplotype, distinct from 23 other Garry oak haplotypes,, reflecting dispersion and recolonization of their current habitat after the last continental glaciers retreated 12,000 years ago. During the current post-glacial period, pollen records suggest that Garry oak forests reached their largest extent during the warm dry era, 5000 to 8000 years ago.

Source

Kanne, R. (2014). Phylogeographic patterns and migration history of Garry oak (Quercus garryana) in western North America.

The advent of the current wetter, cooler climate changed the distribution of many plant species and reduced the range of some. This change in climate probably accounts for the patchy occurrence of Garry oak ecosystems and their associated species. European settlers arriving in the region in the early to mid 1800s described the landscape as plains “scattered”, “dotted”, “thinly clad” or “sprinkled” with oaks. Garry oaks’ ability to survive on well drained soils, on steep south and west facing slopes, and on sites with exposed bedrock accounts for their present distribution in today’s Mediterranean-type climate. The important exception is the deep-soil parkland of southeastern Vancouver Island.

The Garry oak landscape has also been shaped by Indigenous stewardship, primarily with prescribed burns. Approximately 2,000 years ago physical evidence of fire frequency increased during a period that saw large and widespread permanent human settlements around the Salish Sea. Use of fire by Indigenous peoples to modify the landscape and manage overgrowth by grasses, shrubs and trees is now supported by abundant research and is widely recognized.

Source

Environmental Services. Capital Regional District. (May 19, 2021). Biodiversity Protection: Garry Oak Ecosystem Information Sheet. https://www.crd.ca/media/file/may19-2021-ecosysteminfosheets-garryoak5ad44355e7e16533860dff00001065ab

Barsh R & Murphy M. HistoryLink.org Essay 22909. (January 28, 2024). Garry Oaks and Acorns in Native American Cultural Landscapes and Diets. https://www.historylink.org/File/22909

Get to Know Your Garry Oaks

The largest Garry oak by volume in B.C. is at Quamichan Lake near Duncan, but the biggest by circumference (5.75 m around) is at 520 Falkland Road in Oak Bay. At the junction of Mills and West Saanich Roads in North Saanich is a collection of Garry oaks known as the “Genevieve Sangster oaks,” named after the wife of a dairy farmer who promised her that they’d never be cut down. A dozen Garry oak trees catalogued in the UBC Faculty of Forestry’s BC Big Tree Website tower over 20 m high.

Source

Faculty of Forestry & Environmental Stewardship, The University of British Columbia. BC Big Tree Website (5 January 2026). [Accessed 14 January 2026] https://bigtrees.forestry.ubc.ca/bc-bigtree-registry/broadleaves/

Garry oaks can be found in many neighbourhoods in Greater Victoria. There are also numerous parks and public gardens where you can enjoy Garry oaks and their associated meadows. Meadow flowers bloom in succession March to June giving way to grasses through the summer months. Remember to stay on established paths and do not pick flowers or remove acorns or other vegetation during your visit. Where dogs are allowed, ensure they stay with you on established paths and do not dig in or trample the meadows. Below are a few parks to enjoy Garry oak trees and ecosystems.

The Woodland Trail at Government House

The Horticultural Centre of the Pacific

Gulf Islands National Park Reserve

Garry Oak Maps

Historic Southern Vancouver Island

Source

Lea, T. Davidsonia 17(2):34–50 (2006). Historical Garry Oak Ecosystems of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, pre-European Contact to the Present.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285313724_Historical_Garry_oak_ecosystems_of_Vancouver_Island_British_Columbia_pre-European_contact_to_the_present

Central Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands

The Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team website offers additional maps of the distribution of Garry oak ecosystems on Central Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands.

Cowichan Valley and Saltspring Island

Nanaimo, Parksville and Nanoose Bay

Comox, Denby Island and Hornby Island

Cultural Importance

Garry oak ecosystems play an important role in lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ cultural heritage and their connections to living remnants of the lands as they were managed pre-European settler colonization. In the Capital Regional District, remnants of the Garry oak ecosystem make up a large part of the urban forest on the traditional territory of the lək̓ʷəŋən speaking peoples known today as the Songhees and Xwsepsəm (Kosapsom) First Nations, and the W̱SÁNEĆ people encompassing the five local communities: BO,ḰE,ĆEN (Pauquachin), MÁLEXEȽ (Malahat), W̱ JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip), W̱,SIKEM (Tseycum), and S,ȾAUTW̱ (Tsawout), who have worked on this land since time immemorial and whose historical relationship to the land and territories continues to this day.

Prior to European settlement, most of the land that now encompasses southeastern Vancouver Island was dominated by Garry oak ecosystems largely from Indigenous agroecological land management over thousands of years which formed the oak savannah. In the absence of these activities, the landscape would be dominated by closed stands of Douglas-fir and Grand fir.

The Garry oak ecosystem is valued for its cultural history and traditions, and for the Kwetlal (camas) food production system, which was an important source of nourishment. Camas bulbs were historically a primary source of carbohydrates; baked in pits, they taste somewhat like a pear. Many medicines were made from other trees and plants in the ecosystem. Ethnographic studies from the late 1800s to mid-1900s suggest that Garry oak acorns, which are very high in tannins, were not a prominent part of the Coast Salish peoples’ diet, although acorn harvesting and preparation from a variety of oak species is well documented among Indigenous peoples further south.

Work is underway led by First Nations knowledge keepers across the range of Garry oak ecossytems. Cheryl Bryce, a member of the Songhees Nation, and Director of Local Services including Lands Management as a traditional knowledge holder, reinstating harvesting in the meadows for food and medicines, as well as removing invasive plants and educating First Nations and their allies. First Nations women are the backbone of the Kwetlal food system by managing it for centuries and maintaining their connections to their homelands with traditional laws and practices. The Garry oak ecosystem provides Indigenous youth a direct connection to their ancestors and is significant for the continuation and passing of knowledge as traditions change.

Local family groups of Indigenous peoples tended the Garry oak ecosystems, using fire and cultivation as management tools. Garry oaks and the plants that grow with them adapted to frequent fires. Fire is important because it allows oaks to occupy deeper soils, where conifers might out-compete them. Oaks are favoured over conifers and annuals, and perennial plants over shrubs in places that often burn.

Fire was used to burn the plants under the oaks throughout their range to maintain open prairie, to make hunting easier, and to allow the land to produce more food. The edible bulbs of kwetlal (camas) and other species were the focus of the plant harvest. Kwetlal was so important in their diet that families had their own plots of woodland where they owned the harvest.

Deer in Garry oak ecosystems were also important to First Peoples. Blacktail deer are still residents of oak habitat, and Roosevelt elk formerly roamed southeastern Vancouver Island. These animals helped maintain the open character of the Garry oak landscape by suppressing some oak regeneration.

The continued stewardship of Garry oak ecosystems is an act of recognition, appreciation, and support for historic Indigenous land management, maintaining a connection for Indigenous youth to their ancestors, and preserving an opportunity for ongoing management. Unfortunately, Garry oak ecosystem patches have become fragmented and degraded due to land development and the replacement of Garry oak trees with non-native species. Restoring stewardship practices rooted in Indigenous knowledge, including lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples and in best ecosystem management practices—such as replanting Garry oak seedlings, restoring Garry oak ecosystem plant communities, and and retaining declining or dead Garry oaks for the dedication of wildlife snags—can lead to improved cultural, social and environmental outcomes.

European explorers and settlers were attracted to the aesthetic qualities of the landscape around the future site of Victoria with its open, mixed forest of oaks and meadows and rocky uplands. Superlatives from Captain George Vancouver include “as enchantingly beautiful as the most elegantly finished pleasure ground in Europe.” And James Douglas wrote “It appears to be a perfect Eden in the midst of the dreary wilderness of the Northwest coast…” reflecting contemporary English taste for a pastoral, park-like landscape. However, during an interview with Focus Magazine, “Caring for Kwetlal in Meegan”, Cheryl Bryce notes, “What the first settlers didn’t realize (or more accurately, refused to recognize), however, was that the meadows were a managed landscape kept clear of brush and Douglas fir through use of fire, weeding and selective harvesting” by Bryce’s ancestors.

Source

Bryce, Cheryl. Open Space (2019) Meegan. Online On Land. [Accessed 6 July 2023] https://vimeo.com/405250132.

Acker, Maleea. Focus Magazine (2020) Caring for Kwetlal in Meeqan. [Accessed July 18 2023] https://www.focusonvictoria.ca/earthrise/caring-for-kwetlal-in-meegan-r20/

The oak landscape has continued to be important for aesthetics and as a contribution both to the sense of place and to the regional identity of Victorians. Emily Carr, esteemed west coast artist, grew up in the Garry oak meadow and described our Easter lilies (Erythornium oreganum) as “the most delicately lovely of all flowers,” and “in all your thinkings you could picture nothing more beautiful than our lily field.” Some feel that Garry oak groves should be preserved to “serve the whole community’s spiritual needs, as well as for themselves and the spirit they embody.” There is fond local appreciation of the spectacular wildflower shows that the meadows exhibit. Successive waves, in a palette of blue, mauve, white, and gold, rush through their spring presentation over a three or four month flowering period.

From 1843 onwards, colonists irreversibly altered the landscape through agricultural activity, settlement of the land and urban expansion. Garry oak trees proved a disappointment as a timber resource relative to the English oak in wide use in the British Isles. But they became iconic in the built landscape, important to the civic ideal of a green and beautiful city and unique to Victoria’s landscape.

In 1907 and 1908 John Charles Olmsted designed a 465 acre subdivision—the Uplands—for real estate developer William Gardner. Olmsted prepared a detailed survey of the land and ensured that the lots and roads would work with the natural topography and that significant landscape features, including existing Garry oak trees and bay views, were preserved. Olmsted prepared innovative guidelines for protective deed restrictions to retain the carefully designed character, covenants that are now enforced by the City of Oak Bay. On August 19, 2019, the Government of Canada designated Uplands as a National Historic Site.

Source

Cavers, Matt. BC Studies, No. 163 (Autumn 2009) “Victoria’s Own Oak Tree”: A Brief Cultural History of Victoria’s Garry Oaks After 1843. https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/bcstudies/article/view/280

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Uplands. [Accessed 14 January 2026]. https://www.tclf.org/uplands

The Uplands Neighbourhood Association. History of Uplands. [Accessed 14 January 2026]. https://uplandsneighbourhood.com/history/

Ecological Importance

Garry oak supports a unique ecosystem in its Northern habitat where it serves as the keystone species. The trees and associated ecosystems in this region have a local genetic adaptation to the environment and its associated species community would be difficult and costly to re-introduce if lost.

The open oak woodlands are home to a diverse bird community, both in summer and winter. Nest-holes, acorns, and open country habitat are among the benefits that the oak woodlands provide. Lewis’ Woodpecker has disappeared and other birds of concern include Western Bluebird and Band-tailed Pigeon. Mammals from deer to mice are abundant, although the number of mammal species is lower than expected because many mainland species have not managed to colonize the islands. Sunny rock outcrops are a favoured basking place for garter snakes and alligator lizards, and the rare, little-known sharp-tailed snake also inhabits these ecosystems. A great variety of insects and spiders appreciate and depend on the Garry oak warm climate. The Propertius dusky-wing butterfly is completely dependent on Garry oak for larval growth and is considered a vulnerable species. Many invertebrates, including robber flies, butterflies, and seed bugs are restricted to these sunny, coastal meadows. A subspecies of large marble butterfly has already gone extinct. The Perdiccas checkerspot butterfly is no longer found in British Columbia, and Taylor’s checkerspot has been reduced to two populations, one of which is on Hornby Island.

Source

Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team. Species at Risk Fact Sheets. [Accessed 14 January 2026]. https://goert.ca/about/species-at-risk/species-at-risk-field-manual/

Erickson, W. Conservation Data Centre, Wildlife Branch. BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. (1993). Ecosystems in British Columbia at Risk Series: Garry oak Ecosystems. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/conservation-data-centre/publications/erickson_garry_oak.pdf

Irregularly wooded landscapes are called ‘parklands’. The term ‘meadows’ describes the open areas, particularly appropriate in spring and summer when they are lush with bright wildflowers: blue Kwetlal (camas), white Easter lily, and yellow western buttercup. Other fascinating species are satin flower, chocolate lily, and little monkeyflower. Parts of the landscape also feature shrub stands of snowberry and ocean spray. Rock outcrops support scattered shrubby oaks, along with licorice fern, rock mosses, and grasses such as Idaho fescue and California oatgrass. These grasses evoke an image of the southern origin of the Garry oak ecosystems.

Within Garry oak ecosystems, the combined effect of vegetation and dry climate produces special soils with organically enriched upper layers. These dark-coloured soils, in marked contrast to the poorer, reddish-brown soils of surrounding coniferous forests, favour the relatively shallow-rooting herbaceous understory vegetation.

The Greater Victoria area has a high concentration of rare species when compared to the rest of the province. Garry oak ecosystems have been identified as a “hot spot” of biological diversity. Christmas Hill, part of the Swan Lake Nature Sanctuary, has been designated a Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) by the Canadian KBA Coalition. This ecosystem is the most diverse terrestrial ecosystems in British Columbia, containing species ranked “at risk” by the Province of British Columbia to loss or serious depletion.

In addition to the rarities they contain, the designation reflects their limited extent, the significance of their biodiversity from a provincial perspective, and the trend of accelerating habitat loss. Our position at the northern margin of the Californian flora results in a range of species that is one of the most interesting in Canada. Attractive, but now rare, plant species such as Howell’s triteleia, golden paintbrush, deltoid balsamroot, and dozens of others highlight the importance of this biotic zone.

For a description of the flora within the Garry oak ecosystem see the report by Matt Fairbarns (Aruncus Consulting) on the E-Flora Atlas of BC.

Source

Klinkenberg, Brian (Editor). Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. (2020) E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants of British Columbia [eflora.bc.ca]. [Accessed 14 January 2026]. https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Quercus%20garryana

The University of Victoria’s “Plan2Adapt” climate modeling for the South Island forecasts an average temperature rise exceeding 3 degrees Celsius by 2050, compared to the 1960-1990 baseline. This increase will likely lead to more frequent heat domes and severe droughts. Garry oak ecosystems, inherently adapted to hot, dry summers, serve as essential nature-based solutions to mitigate the urban heat island effect, particularly where vulnerable people live.

Impacts of climate change on human health in BC have been graphically and tragically revealed — for example, during the “heat dome” of 2021 when more than 600 people died. Since then, oppressive conditions have become the norm in many urban areas during the summer months, particularly for seniors, people with disabilities, low-income people, and people with various health conditions.

Source

Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium (PCIC). (2024). Climate projections for the capital region. https://www.crd.ca/media/file/climateprojectionscapitalregion2024

Michael Egilson (Chair, Death Review Panel). (2022). Extreme Heat and Human Mortality:A Review of Heat-Related Deaths in B.C. in Summer 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/extreme_heat_death_review_panel_report.pdf

In the City of Victoria, 75% of the urban forest is on private property. It is important to remember that Garry oaks are big contributors to mitigating urban heat island effects in areas largely characterized by pavement and concrete. That is especially the case where large oak trees currently exist and air conditioners in residences do not. This is accomplished by larger trees with wide crowns and abundant leaf area, and because of their incredible ability to endure harsh urban conditions in drought and high temperatures.

The cooling that oaks provide is from shading heat-absorbing surfaces and also from transpiration: cooling the air with the release of water by evaporation through the soil and through the tree transpiring through leaves’ stomata. Strength is not only in the size of tree canopies, but in the distribution of tree canopy proximate to where people live, work, play, and go to school.

The natural regeneration of Garry oaks is facing significant challenges, largely due to human activities. Key factors include the restriction of Indigenous fire management, urban expansion, increased recreational pressures, the prevalence of forest pathogens, invasive species that threaten biodiversity, and the rising incidence of hot, dry summers. Areas further south on Vancouver Island and the Southern Gulf Islands have experienced declines in conifer stands adjacent to urban developments, consistent with climate modeling predictions.

The decline of species such as western redcedar, grand fir, western hemlock, western yew, and Douglas fir is occurring at a troubling rate, impacting both forest management and the communities dependent on these ecosystems.

Conversely, established Garry oak stands exhibit remarkable resilience to drought and high temperatures, thriving even on rocky outcrops with shallow soils. Garry oaks possess deep taproots and well-developed lateral roots, making them resilient to wind and environmental stress. As a long-lived keystone species, Garry oak has played a vital role in supporting biodiversity over the past 8,000 years. Protecting existing Garry oak ecosystem patches, implementing suitable management practices, and expanding these areas are crucial for sustaining numerous organisms.

Ecosystem threats

Garry oak ecosystems are restricted primarily to the southeast coast of Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands. These ecosystems occupy only a small portion of the Coastal Douglas-fir moist maritime biogeoclimatic zone (CDFmm), which itself comprises only 0.3 percent of the land area of the Province and is a conversvation concern.

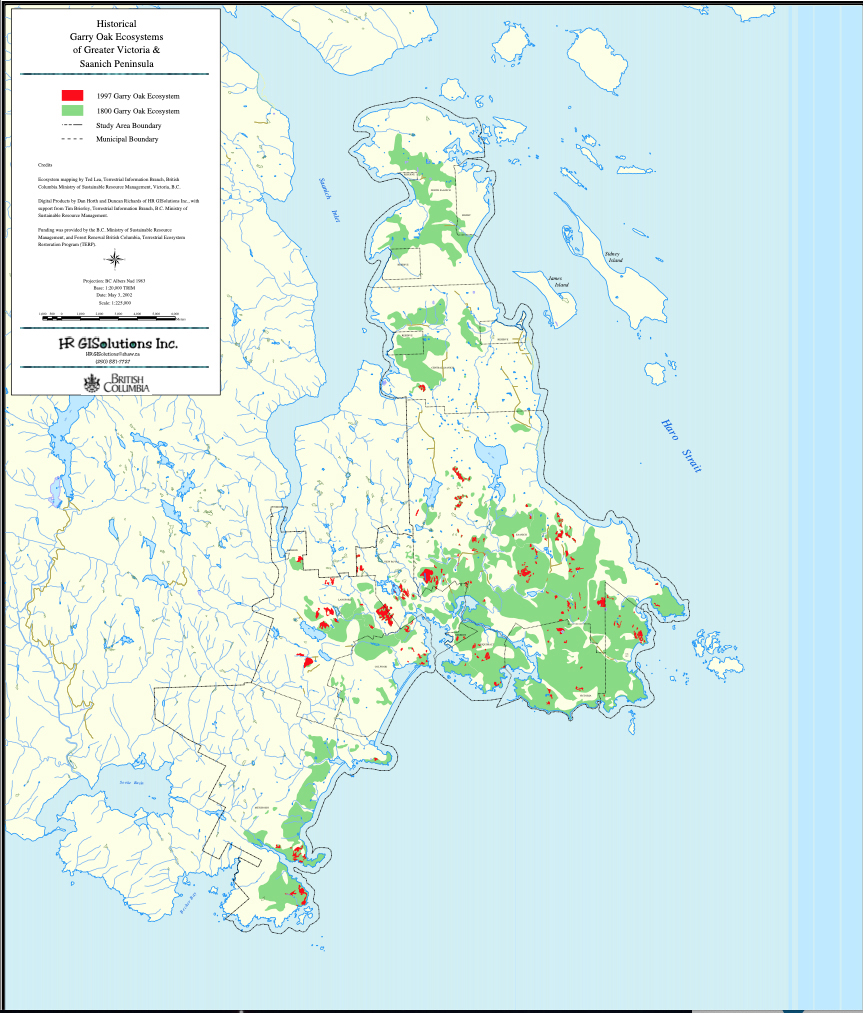

During the last 150 years, agricultural and urban development have consumed substantial areas of the natural landscape. Overall, environmental colonialism and urban development have had a major impact. The largest continuous occurrence of Garry oak woodlands was formerly in the urban center of Greater Victoria, a region that is now almost completely developed. Parkland and meadows, once common in this area, are in extreme peril. As has been documented at Helliwell Provincial Park on Hornby Island, suppression of low-intensity fire has allowed Douglas-fir to invade areas once dominated by Garry oak.

According to the GOERT, as of 2006, coverage of the ecosystem had been reduced to 1,589 hectares from 15,249 hectares. Deep-soil meadows have suffered also; from 12,009 hectares pre-European settlement to 175 hectares in 2006. Very little of the original Garry oak landscape remains in an unaltered state.

The trend continues, with many developments imminent. Today, Duncan, Nanaimo, Hornby Island, Salt Spring Island, and Courteney all have Garry oak landscapes threatened by development. Removal of Garry oak trees from building lots is an obvious and immediate way the urban forest is reduced. Although the death may be a slow one – up to 10 years – building out the landscape near oaks can also lead to tree mortality due to: direct damage to the tree or to its root system during construction, compaction of soil and use of impermeable surface materials within the critical root zone, changes in the water table associated with building foundations and resurfacing, and shading Garry oaks through adjacent multistory construction.

Source

Hoffman KM, Wickham SB, McInnes WS, Starzomski BM. Fire 2, 48 (2019). Fire Exclusion Destroys Habitats for At-Risk Species in a British Columbia Protected Area. https://www.mdpi.com/2571-6255/2/3/48

Lea, T. Davidsonia 17(2):34–50 (2006). Historical Garry Oak Ecosystems of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, pre-European Contact to the Present. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285313724_Historical_Garry_oak_ecosystems_of_Vancouver_Island_British_Columbia_pre-European_contact_to_the_present

The impact of introduced and invasive species

Overgrazing by domestic and feral livestock, including pigs, sheep, goats, cattle and horses, as well as introduced eastern cottontail, and recently feral pet rabbits, has caused non-native plant species to become dominant. Residential and agricultural pesticide use can imperil the butterflies and insects dependent on Garry oaks and the sunny coastal meadows.

These introduced plants spread widely after European settlement. Exotics, such as orchard grass and sweet vernal grass may comprise over 30 percent of the total species in Garry oak ecosystems. Rapid spread of Scotch broom has also replaced native plants, changed soil nutrients, and dramatically altered the make-up of these ecosystems. The increased rarity of many native species is another result of these changes. In our region, other “introduced” species that are out-competing native species are English ivy, Himalayan blackberry, daphne, several grasses, European starlings, grey squirrels, gypsy moths, and others.

Source

Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team. Invasive Species. [Accessed 14 January 2026]. https://goert.ca/about/invasive-species/

Conservation

The South Coast Conservation Partnership published a Species at Risk in BC Field Guide in 2016 that provides information on the Species at Risk Act.

How are species at risk status defined?

Extinct – A wildlife species that no longer exists.

Extirpated – A wildlife species that no longer exists in the wild in Canada but exists elsewhere.

Endangered – A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

Threatened – A wildlife species that is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction.

Special Concern – A wildlife species that may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

The BC Conservation Data Centre assigns each species and ecosystem to a red, blue or yellow list based on conservation status rank, which is based on a number of factors. This ranking is used to help set conservation priorities and provide a simplified view of the status of BC’s species and ecosystems. These lists also help to identify species and ecosystems that can be considered for designation as “Endangered” or “Threatened.”

To learn more about species at risk visit BC Species & Ecosystems Explorer and Species at Risk in BC Field Guide 2016

What support is available to help landowner protect critical habitat?

• Tax incentives for “EcoGifts”

• Funding programs (e.g., Habitat Stewardship Fund)

• Conservation Agreements

• Information to assist in land use planning

For detailed information on conservation covenant agreements see: BC Conservation Covenant Handbook